“BattleCamp” by PennyPop: Mobile gaming meets Massively Multiplayer in Ruby

The gaming ecosystem is changing rapidly and some of the most popular games are coming from smaller game studios with a focus on rapid application development to meet ever-changing market trends.

PennyPop, the team behind BattleCamp, is one of these game studios. BattleCamp, a mobile video game with battling monsters, massively multiplayer capabilities (including player-versus-player), real-time combat and chat with beautifully colored artwork has a 4+ rating and over four thousand reviews on the Apple App Store for iOS.

In BattleCamp, you start with a small contingent of your own monsters that you use to battle other monsters with a never ending quest to collect as many as you can. As you progress, you have the option of leveling-up your monsters, gaining more power as you go. Players also have avatars in BattleCamp that can be customized with various appearances as well as costumes.

One of the most interesting things about BattleCamp is the technology that runs the game behind the scenes. It may seem surprising to some to learn that all of BattleCamp’s server-side actions run in Ruby! And we’re not talking about some “fancy” Ruby interpreter here either. No custom patches, no special concurrency hacks or tweaks - just good ol’ MRI.

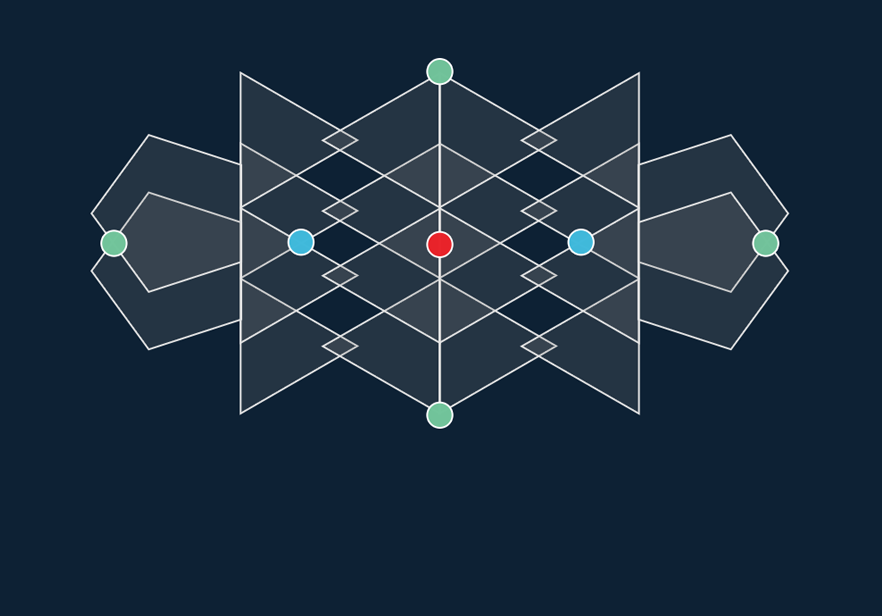

The architecture behind the battling monsters: A tale of two clusters

PennyPop needed a cloud application management platform that would help them maintain a secure, reliable infrastructure without the need for a full time systems administrator (or two). In addition, the company values keeping a very small team and pushing out features very quickly over nearly everything else, as this allows them to keep pace with a rapidly changing market and earn higher profit margins. By using Engine Yard, the company has been able to scale, configure and deploy with ease since the vast majority of necessary system configuration for web applications and databases is already handled out of the box, leaving very little for PennyPop’s personnel to do other than write great code and build a great game. As a result, PennyPop has been able to implement a Ruby backend capable of processing approximately 40,000 requests per minute using an innovative data storage practice while meeting their business goal of increasing customer demand while maintaining a small, tight team.

PennyPop operates two inter-dependent application clusters for the role-playing game. The first is a standard Ruby on Rails application that acts as an API and data transaction layer. The second cluster is what PennyPop calls their “Virtual World” - a large collection of virtual machines running their EventMachine-powered application, written in Ruby, to which clients (players’ mobile devices) make a persistent TCP connection.

There are two basic types of actions in the game. First, players can manage inventory, perform in-app purchases of items to gain certain conveniences (though nothing game-breaking), manage their quests, and so on.

Secondly, players can speak with others and, most importantly, battle NPCs (non-player characters) and other players.

The first set of actions can be considered “latency-tolerant” - in other words, one or two seconds isn’t a big deal - which makes them perfectly suited to having the client (mobile application) submit an API request.

However, the second set of actions - “real-time” actions - aren’t latency-tolerant at all. When fighting in the game, the actions you submit to - and receive from - the server must feel very fluid and responsive, or the game loses its appeal. This is why PennyPop utilizes a second cluster for EventMachine-based actions.

When a user first logs in to the game, they are initially talking to the API running on Engine Yard. That API then accesses information previously stored in memcached and Amazon’s DynamoDB to figure out which machine and port to send that user to for connecting to one of PennyPop’s “Virtual World” servers. The client then forms a persistent TCP connection to the assigned server and sends events to that server. That server then responds to those events as needed.

Think of it like this: when you check into a hotel, the front desk tells you which room to go into. PennyPop’s infrastructure is much the same. When users first connect to the game, the client is told by the API which server in their Virtual World cluster to form a persistent connection with. This is how PennyPop is able to build a responsive MMO back-end with Ruby that processes roughly 40,000 RPM according to New Relic.

When an action takes place in the game, such as a battle being won or an item being awarded, the Virtual World server on which the player is playing sends an API request to the Rails application stating that the player performed such-and-such an action (e.g. “Player X collected reward Y”). That Rails application then takes care of storing this information inside DynamoDB and sends a response back to the Virtual World application.

With a massive number of players comes massive amounts of data: An innovative data storage practice

PennyPop’s API doesn’t make use of ActiveRecord or anything quite like it; instead, PennyPop opted to create their own data storage layer to “talk to” DynamoDB. However, DynamoDB has an interesting limitation in the amount of information it can store in a specific key. As PennyPop can frequently exceed that with their data model, they’ve developed an interesting approach to storing values that would normally exceed that size limitation.

When a record is retrieved, as with most other key/value stores, the key is simply referenced. However, the value of that key is a zipped (compressed) payload of base64 encoded data. When the BattleCamp API needs to read or manipulate this data, it retrieves it from DynamoDB (utilizing secondary indexes if needed), decompresses it, and decodes the base64 payload. Now PennyPop has a viable representation of their model (user, character, etc.). At this point they can then manipulate the data (update an attribute, add an item, etc.) and base64 encode it again, compress it again, and store the compressed payload in DynamoDB.

This involves a significant amount of CPU overhead each time data needs to be read or written. This means that PennyPop’s infrastructure costs are likely to be a little higher, as they need more CPU resources and virtual machines to handle load.

According to Charles Ju, Founder of PennyPop, “Engine Yard makes the headaches that come with maintaining infrastructure go away. You have a full team for database management, a fully staffed, 24/7 support team that is second to none, and [they are] constantly improving the technology. It would be insane for me to try to replicate that myself. If someone is building a real business, or embarking on a serious endeavor, they should get all the help they can, especially when it’s affordable. And Engine Yard, to a real business, is very affordable. If you’re using Rails, it’s foolish not to use Engine Yard.”

Share your thoughts with @engineyard on Twitter