Using Services to Keep Your Rails Controllers Clean and DRY

We’ve heard it again and again, like a nagging schoolmaster: keep your Rails controllers skinny. Yeah, yeah, we know. But easier said than done, sometimes. Things get complex. We need to talk to some other parts of our codebase or to external APIs to get the job done. Mailers. Stripe. External APIs. All that code starts to add up.

Ah Tss Push It…Push It Down the Stack

If we ask: “where, pray tell, should this code live?”, the answer comes like a resounding chorus: “push it down to the model layer!”

But what if we want to keep our models simple? They should actually reflect the business objects related to our app, according to Domain Driven Design and other approaches.

Time to get custom!

Crack open the old app folder. What do you see? The usual fare? Guess what? Just because Rails comes with six folders doesn’t mean we’re restricted to six types of object. Let’s make some new folders!

At Your Service

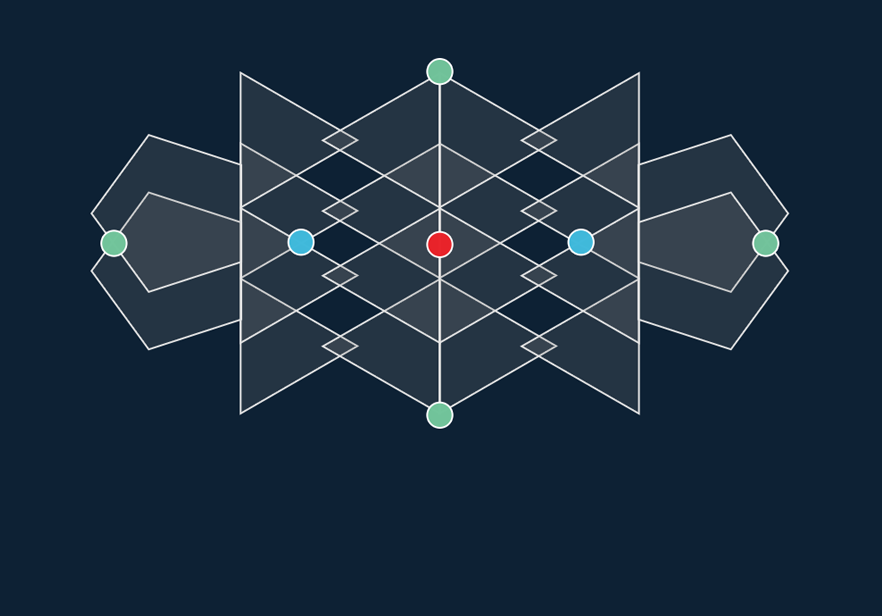

I like to create various kinds of service objects in my Rails app. Tom Pewiński’s recent article in Ruby Weekly does a great job of covering how to write service objects that help complete an action, like create_invoice or register_user. While he puts all of his service objects into a single services folder, I like to get a little more granular. I’ll typically create an actions folder for things like create_invoice, and folders for other service objects such as decorators, policies, and support. I also use a services folder, but I reserve it for service objects that talk to external entities, like Stripe, AWS, or geolocation services.

Here’s how the app folder might look with all of these subfolders in it:

app

|- actions

|- assets

|- controllers

|- decorators

|- models

|- policies

|- services

|- support

|- views

Earning Our Stripes

Let’s give it a try, right now! We’ll make a credit card service that uses the Stripe gem.

We’ll create an app/services folder and touch a credit_card_service.rb inside of it. It’s going to be a Plain Old Ruby Object™ (PORO).

It’s probably a good idea to wrap the calls to the Stripe gem in local methods like external_customer_service and external_charge_service, in case we ever want to switch over to Braintree or something else. On object initialization, we’ll use dependency injection to accept charge amounts, card tokens, and emails. Our service will expose charge! and create_customer! methods to hook our controllers into.

# app/services/credit_card_service.rb

require 'stripe'

class CreditCardService

def initialize(params)

@card = params[:card]

@amount = params[:amount]

@email = params[:email]

end

def charge

begin

# This will return a Stripe::Charge object

external_charge_service.create(charge_attributes)

rescue

false

end

end

def create_customer

begin

# This will return a Stripe::Customer object

external_customer_service.create(customer_attributes)

rescue

false

end

end

private

attr_reader :card, :amount, :email

def external_charge_service

Stripe::Charge

end

def external_customer_service

Stripe::Customer

end

def charge_attributes

{

amount: amount,

card: card

}

end

def customer_attributes

{

email: email,

card: card

}

end

end

Hook it Up

Now we can write some clean, easily maintainable controller code. We keep the registration logic private, and if we ever want to change it, the controller doesn’t have to know anything about it.

# app/controllers/users_controller.rb

class UsersController < ActionController::Base

def create

@user = User.create(user_params)

registration = register_with_credit_card_service

if registration

# Save the id from the Stripe::Customer object

add_customer_id_to_user(registration["id"])

...

else

...

end

end

private

...

def register_with_credit_card_service

CreditCardService.new({

card: params[:stripe_token]

email: params[:user][:email]

}).create_customer

end

def add_customer_id_to_user(id)

@user.update_attributes(external_customer_id: id)

end

end

Test It Out

Since we’re just using a PORO, this should be nice and easy to test. Let’s make a test/services folder. If you want to add its contents to your rake tasks, try this. Let’s assume that we already have a test_helper.rb that includes the Rails helpers in ActiveSupport::TestCase and mocha.

# test/services/credit_card_service_test.rb

require 'test_helper'

class CreditCardServiceTest < ActiveSupport::TestCase

test 'it creates charges' do

params = {

amount: 500,

card: 'TOKEN'

}

Stripe::Charge.expects(:create).with(params).returns(true)

# This will return false if it fails

charge = CreditCardService.new(params).charge

assert charge

end

test 'it creates customers' do

params = {

email: '[email protected]',

card: 'TOKEN'

}

Stripe::Customer.expects(:create).with(params).returns(true)

# This will return false if it fails

customer = CreditCardService.new(params).create_customer

assert customer

end

end

Keep It Clean

The last thing you want in your Rails app is a bunch of complicated controllers that are hard to change. Though it may sound pedantic, those voices chanting “Skinny Controller, Fat Model” are right. It’s easy to get caught in the trap of answering “where should I put this code” with “let’s open the app folder and see what cubbies I was given”. Don’t be afraid to take your Rails project by the horns! You can create your own actions, decorators, support objects, and services. Start including these patterns in your Rails app, and your code will come out clean and DRY: so fresh, so clean!

Share your thoughts with @engineyard on Twitter