Pets vs. Cattle

I was one of the original developers on Orchestra, the PHP PaaS that Engine Yard acquired in 2011. Many of our customers were using PaaS for the first time, having come from very traditional hosting backgrounds. They were used to uploading things to FTP servers and editing config files remotely — a practice that is still widespread, despite the popularity of Git and sites like The Twelve-Factor App. It is made all the more prevalent by the fact that many off-the-shelf PHP apps are quite old, and still assume this sort of deployment scenario.

Now, this isn’t to be scoffed at. Traditional system administration is based around the notion of physical machines. To add a new machine to a cluster, you might have to purchase it up front, configure it in your offices, and then drive it to your colocation data centre to install it. That could easily take a few weeks. And if that machine later develops a problem, you do your best to fix the issue via SSH. And if that’s not possible, you might have to drive back out to your colocation data centre to fix it or replace it.

I used to manage my servers like this. In fact, I still remember when I was cutting my teeth on system administration and all my servers had cute names. I chose to name them after characters from Douglas Hofstadter’s book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Tortoise was my main Apache httpd instance, Achilles was running Squid in a reverse proxy mode, Crab was running MySQL, and Genie was my SMTP smart host. Each machine had a customised motd, with a colourful ASCII art banner and a quote from the book.

I was proud of myself for separating out the different parts of my setup. I lovingly nurtured each machine. I would install packages on them, configure them, test them, and so on. And when some problem occurred I would nurse them back to health, all the while being careful to take notes on what actions I performed. Then, if disaster struck, I would be able to recreate them from scratch. When the turnaround on a new server is measured in weeks, you tend to them with extreme care.

But this isn’t how you do things in the cloud.

Discovering an Analogy

With the advent of virtualisation, there’s no need to deal with physical hardware, and no need to travel anywhere. In fact, it’s often easier to just terminate problematic servers from your administration console. You can then relaunch a new server from a catalogue of server images. This process can now take minutes, instead of weeks.

And to make this possible, most cloud providers are built around the concepts of shared-nothing architecture, stateless file systems, configuration automation and repeatability, and so on. But these concepts can seem very restrictive if you’re coming from a traditional hosting background. And for a long time, I struggled to explain the differences to our customers. Particularly, I found it hard to justify why this way of doing things was better.

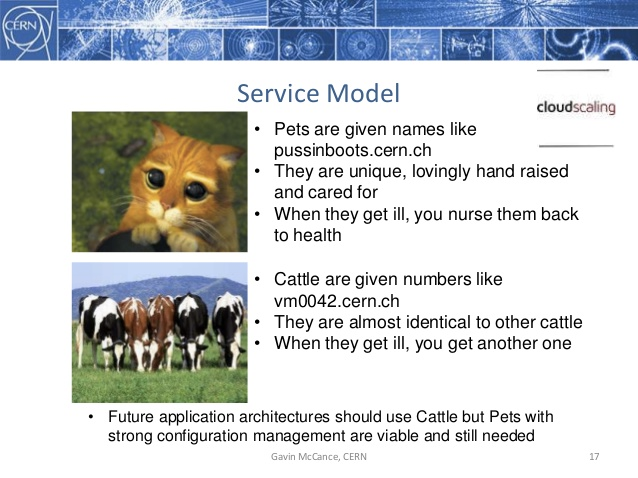

But then Massimo at IT 2.0 introduced me to this:

The difference between the pre-virtualisation model and the post-virtualisation model can be thought of as the difference between pets and cattle. Pets are given loving names, like pussinboots (or in my case, Tortoise, Achilles, etc.). They are unique, lovingly hand-raised, and cared for. You scale them up by making them bigger. And when they get sick, you nurse them back to health. Whereas cattle are given functional identification numbers like vm0042. They are almost identical to each other. You scale them out by getting more of them. And when one gets sick, you replace it with another one.

As Massimo points out, once you have that analogy in mind, it’s easy to determine whether you’re dealing with pets or cattle. Ask yourself this: what would happen if several of your servers went offline right now? If such a thing would go unnoticed by your end-users, then you are dealing with cattle. If it would cause a major disruption for your end-users, you have pets.

It also provides a template for thinking about your architecture. You can look at a server and ask yourself: what would I do if this got sick? The answer you’re looking for is: terminate it immediately and replace it with a new one. If you’re worrying about backups, data dumps, scheduled downtime, or tedious manual reconfiguration, that should be a red flag.

But the post-virtualisation model is still relatively new, and many legacy apps are going to be around for a while yet. If you have a complex setup, you might even need to keep both pets and cattle on your server farm. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist.) Fortunately, Engine Yard supports both. If you need to keep pets, you can keep pets. We can help you with that and we can nurture them on your behalf. But if you want to take advantage of some of the more advanced features of our platform and enjoy the real benefits of what the cloud has to offer, we strongly urge you to consider switching to cattle. (And we can help you with that too!)

The Rest of the Story

Now that you know the difference between a pet server and a cattle server, you may be wondering how to make cattle servers, and especially how to develop applications for them. If so, then you’re in luck, because this post is the first in a series that explains just that!

The next post explains how the counterintuitive notion of configuring a server before you boot it is not only possible, but actually leads to immense gains for cloud server deployment.

Meanwhile, I hope you enjoyed reading about the pets vs. cattle analogy. Were you familiar with it previously, or are you just learning about it for the first time? Do you think that the analogy accurately describes your own experiences with servers, or can you think of an alternative? I’d love to hear from you, so please comment below.

Share your thoughts with @engineyard on Twitter